The following has been accepted for presentation at ASCILITE’2019. It’s based on work described in earlier blog posts.

Click on the images below to see full size.

Abstract

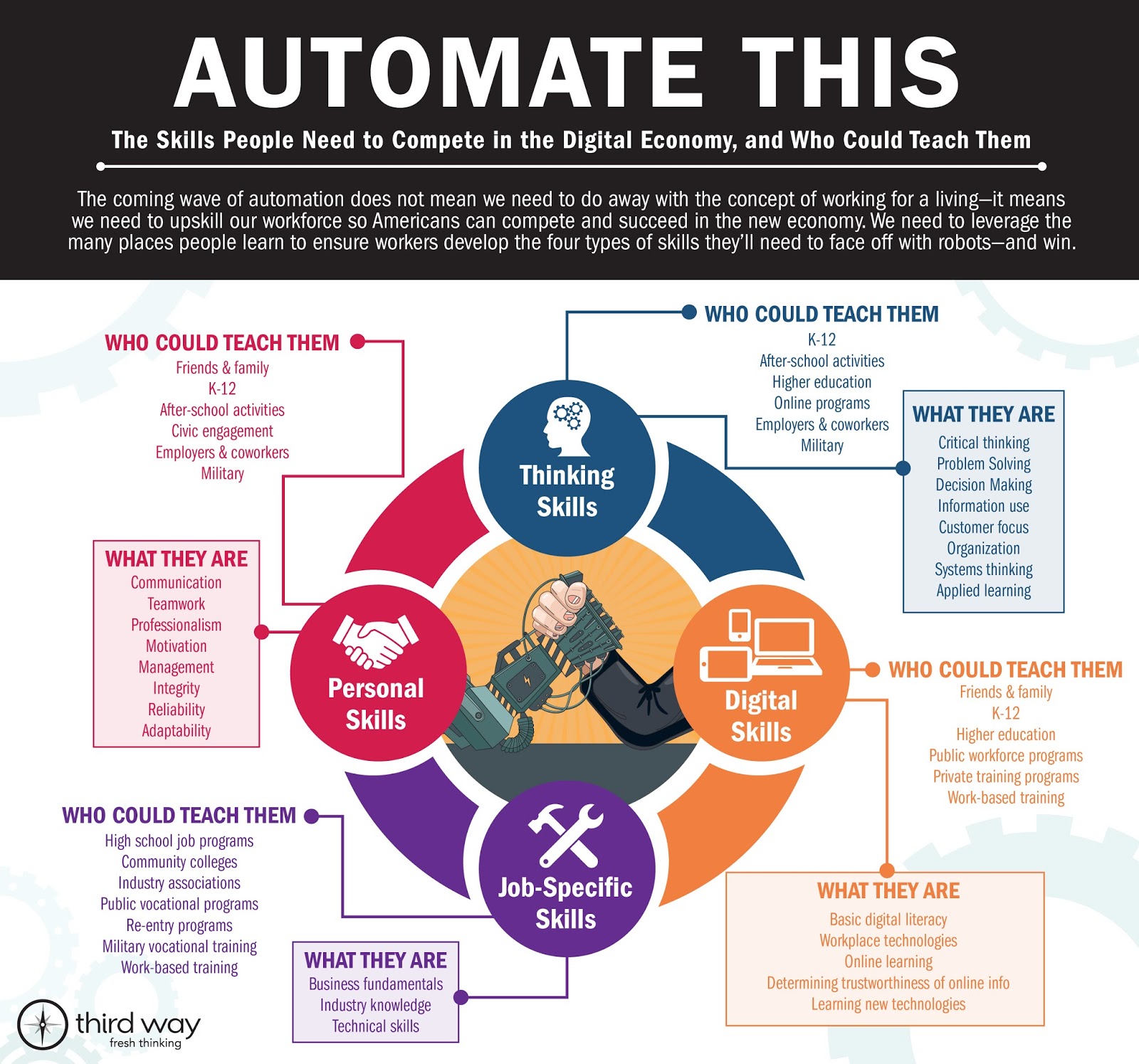

Higher education is being challenged to improve the quality of learning and teaching while at the same time dealing with challenges such as reduced funding and increasing complexity. Design for learning has been proposed as one way to address this challenge, but a question remains around how to sustainably harness all the diverse knowledge required for effective design for digital learning. This paper proposes some initial design principles embodied in the idea of Context-Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA) as one potential answer. These principles arose out of prior theory and work, contemporary digital learning practices and the early cycles of an Action Design Research process that has developed two digital ensemble artefacts employed in over 30 courses (units, subjects). Early experience with this approach suggests it can successfully increase the level of design knowledge embedded in digital learning experiences, identify and address shortcomings with current practice, and have a positive impact on the quality of the learning environment.

Keywords: Design for Learning, Digital learning, NGDLE.

Introduction

Learning and teaching within higher education continues to be faced with significant, diverse and on-going challenges. Challenges that increase the difficulty of providing the high-quality learning experiences necessary to produce graduates of the standard society is expecting (Bennett, Lockyer, & Agostinho, 2018). Goodyear (2015) groups these challenges into four categories: massification and the subsequent diversification of needs and expectations; growing expectations of producing work-ready graduates; rapidly changing technologies, creating risk and uncertainty; and, dwindling public funding and competing demands on time. Reconceptualising teaching as design for learning has been identified as a key strategy to sustainably, and at scale, respond to these challenges in a way that offers improvements in learning and teaching (Bennett et al., 2018; Goodyear, 2015). Design for learning aims to improve learning processes and outcomes through the creation of tasks, environments, and social structures that are conducive to effective learning (Goodyear, 2015; Goodyear & Dimitriadis, 2013). The ability of universities to develop the capacity of teaching staff to enhance student learning through design for learning is of increasing financial and strategic importance (Alhadad, Thompson, Knight, Lewis, & Lodge, 2018).

Designing learning experiences that successfully integrate digital tools is a wicked problem. A problem that requires the utilisation of expert knowledge across numerous fields to design solutions that respond appropriately to the unique, incomplete, contextual, and complex nature of learning (Mishra & Koehler, 2008). The shift to teaching as design for learning requires different skills and knowledge, but also brings shifts in the conception of teaching and the identity of the teacher (Gregory & Lodge, 2015). Effective implementation of design for learning requires detailed understanding of pedagogy and design and places cognitive, emotional and social demands on teachers (Alhadad et al., 2018). The ability of teachers to deal with this load has significant impact on learners, learning, and outcomes (Bezuidenhout, 2018). Academic staff report perceptions that expertise in digital technology and instructional design will be increasingly important to their future work, but that these are also the areas where they have the least competency and the highest need for training (Roberts, 2018). Helping teachers integrate digital technology effectively into learning and teaching has been at or near the top of issues facing higher education over several years (Dahlstrom, 2015). However, the nature of this required knowledge is often underestimated by common conceptions of the knowledge required by university teachers (Goodyear, 2015). Responding effectively will not be achieved through a single institutional technology, structure, or design, but instead will require an “amalgamation of strategies and supportive resources” (Alhadad et al., 2018, pp. 427-429). Approaches that do not pay enough attention to the impact on teacher workload run the risk of less than optimal learner outcomes (Gregory & Lodge, 2015).

Universities have adopted several different strategies to ameliorate the difficulty of successfully engaging in design for digital learning. For decades a common solution has been that course design, especially involving the adoption of new methods and technologies, should involve systematic planning by a team of people with appropriate expertise in content, education, technology and other required areas (Dekkers & Andrews, 2000). The use of collaborative design teams with an appropriate, complementary mix of skills, knowledge and experience mirrors the practice in other design fields (Alhadad et al., 2018). However, the prevalence of this practice in higher education has been low, both then (Dekkers & Andrews, 2000) and now. The combination of the high demand and limited availability of people with the necessary knowledge mean that many teaching staff miss out (Bennett, Agostinho, & Lockyer, 2017). A complementary approach is professional development that provides teaching staff with the necessary knowledge of digital technology and instructional design (Roberts, 2018). However, access to professional development is not always possible and funding for professional development and training has rarely kept up with the funding for hardware and infrastructure (Mathes, 2019). There has been work focused on developing methods, tools and repositories to help analyse, capture and encourage reuse of learning designs across disciplines and sectors (Bennett et al., 2017). However, it appears that design for learning continues to struggle to enter mainstream practice (Mor, Craft, & Maina, 2015) with design work undertaken by teachers apparently not including the use of formal methods or systematic representations (Bennett et al., 2017). There does, however, remain on-going demand from academic staff for customisable and reusable ideas for design (Goodyear, 2005). Approaches that respond to academic concerns about workload and time (Gregory & Lodge, 2015) and do not require radical changes to existing work practices nor the development of complex knowledge and skills (Goodyear, 2005).

If there are limitations with current common approaches, what other approaches might exist? Leading to the research question of this study:

How might the diverse knowledge required for effective design for digital learning be shared and used sustainably and at scale?

An Action Design Research (ADR) process is being applied to develop one answer to this question. ADR is used to describe the design, development and evaluation of two digital artefacts – the Card Interface and the Content Interface – and the subsequent formulation of initial design principles that offer a potential answer to the research question. The paper starts by describing the research context and research method. The evolution of each of the two digital artefacts is then described. This experience is then abstracted into six design principles encapsulated in the concept of Context-Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA). Finally, the conclusions and implications of this work are discussed.

Research context and method

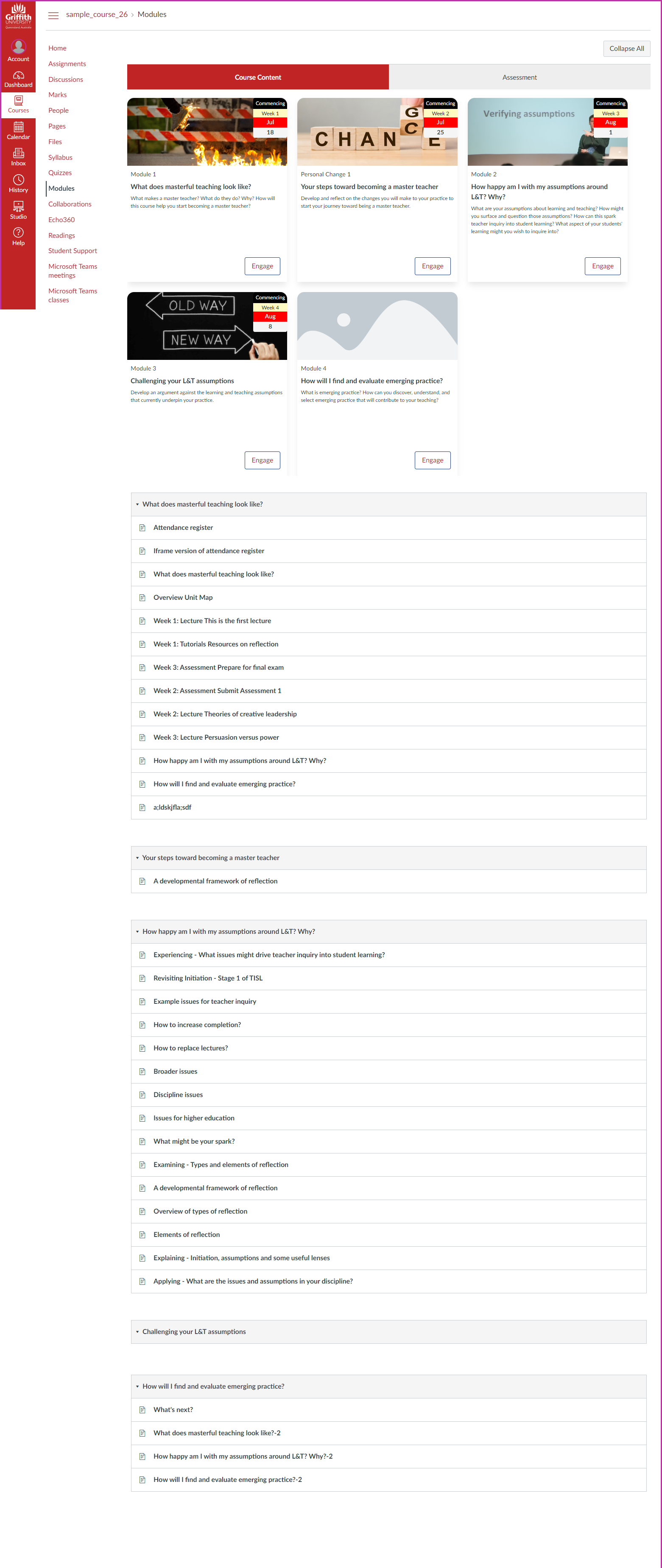

This research project started in late 2018 within the Learning and Teaching (L&T) section of the Arts, Education and Law (AEL) Group at Griffith University. Staff within the AEL L&T section work with the AEL’s teachers to improve the quality of learning and teaching across about 1300 courses (units, subjects) and 68 programs (degrees). This work seeks to bridge the gaps between the macro-level institutional and technological vision and the practical, coal-face realities of teaching and learning (micro-level). In late 2018 the macro-level vision at Griffith University consisted of current and long-term usage of the Blackboard Learn Learning Management System (LMS) along with a recent decision to move to the Blackboard Ultra LMS. In this context, a challenge was balancing the need to help teaching staff continue to improve learning and teaching within the existing learning environment while at the same time helping the institution develop, refine, and achieve its new macro-level vision. It is within this context that the first offering of Griffith University’s Bachelor of Creative Industries (BCI) program would occur in 2019. The BCI is a future-focused program designed to attract creatives who aspire to a career in the creative industries by instilling an entrepreneurial mindset to engage and challenge the practice and business of the creative industries. Implementation of the program was supported through a year-long strategic project including a project manager and educational developer from the AEL L&T section working with a Program Director and other academic staff. This study starts in late 2018 with a focus on developing the course sites for the seven first year BCI courses. A focus of this work was to develop a striking and innovative design that mirrored the program’s aims and approach. A design that could be maintained by the relevant teaching staff beyond the project’s protected niche. This raised the question of how to ensure that the design knowledge required to maintain a digital learning environment into the future would be available within the teaching team?

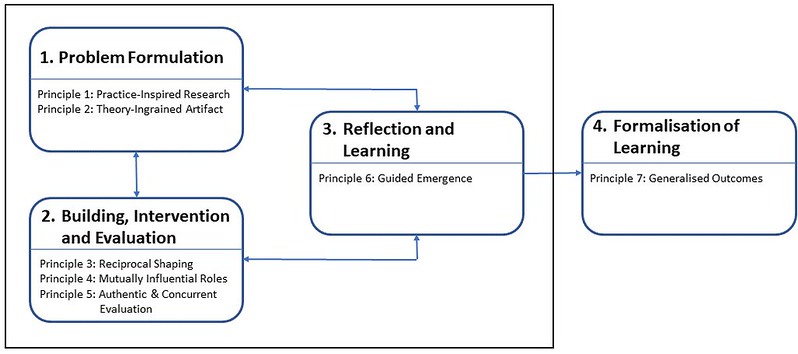

To answer this question an Action Design Research (Sein, Henfridsson, Purao, & Rossi, 2011) process was adopted. ADR is a merging of Action Research with Design Research developed within the Information Systems discipline. ADR aims to use the analysis of the continuing emergence of theory-ingrained, digital artefacts within a context as the basis for developing generalised outcomes, including design principles (Sein et al., 2011). A key assumption of ADR is that digital artefacts are not established or fixed. Instead, digital artefacts are ensembles that arise within a context and continue to emerge through development, use and refinement (Sein et al., 2011). A critical element of ADR is that the specific problem being addressed – design of online learning environment for courses within the BCI program – is established as an example of a broader class of problems – how to sustainably and at scale share and reuse the diverse knowledge required for effective design for digital learning (Sein et al., 2011). This shift moves ADR work beyond design – as practised by any learning designer – to research intending to provide guidance to how others might address similar challenges in other contexts that belong to the broader class of design problems.

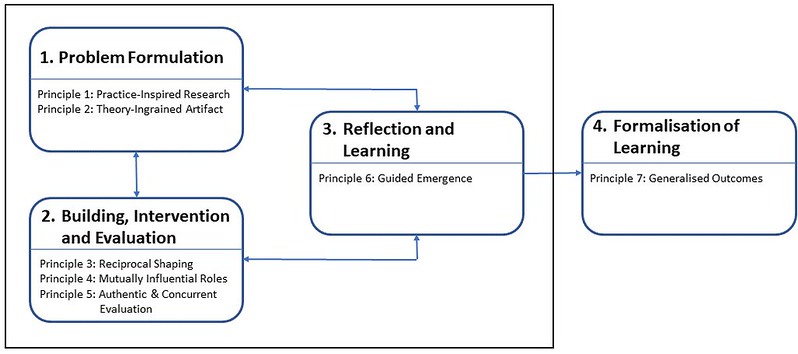

Figure 1 provides a representation of the ADR four-stage process and the seven principles on which ADR is based. Stages 1 through 3 represent the process through which ensemble digital artefacts are developed, used and evolved within a specific context. The next two sections of this paper describe the emergence of two artefacts developed for the BCI program as they cycled through the first three ADR stages numerous times. The fourth stage of ADR – Formalisation of Learning – aims to abstract the situated knowledge gained during the emergence of digital artefacts into design principles that provide guidance for addressing a class of field problems (Sein et al., 2011). The third section of this paper formalizes the learning gained in the form of six initial design principles structured around the concept of Contextually Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA).

Figure 1 – ADR Method: Stages and Principles (adapted from Sein et al., 2011, p. 41)

Card Interface (artefact 1, ADR stages 1-3)

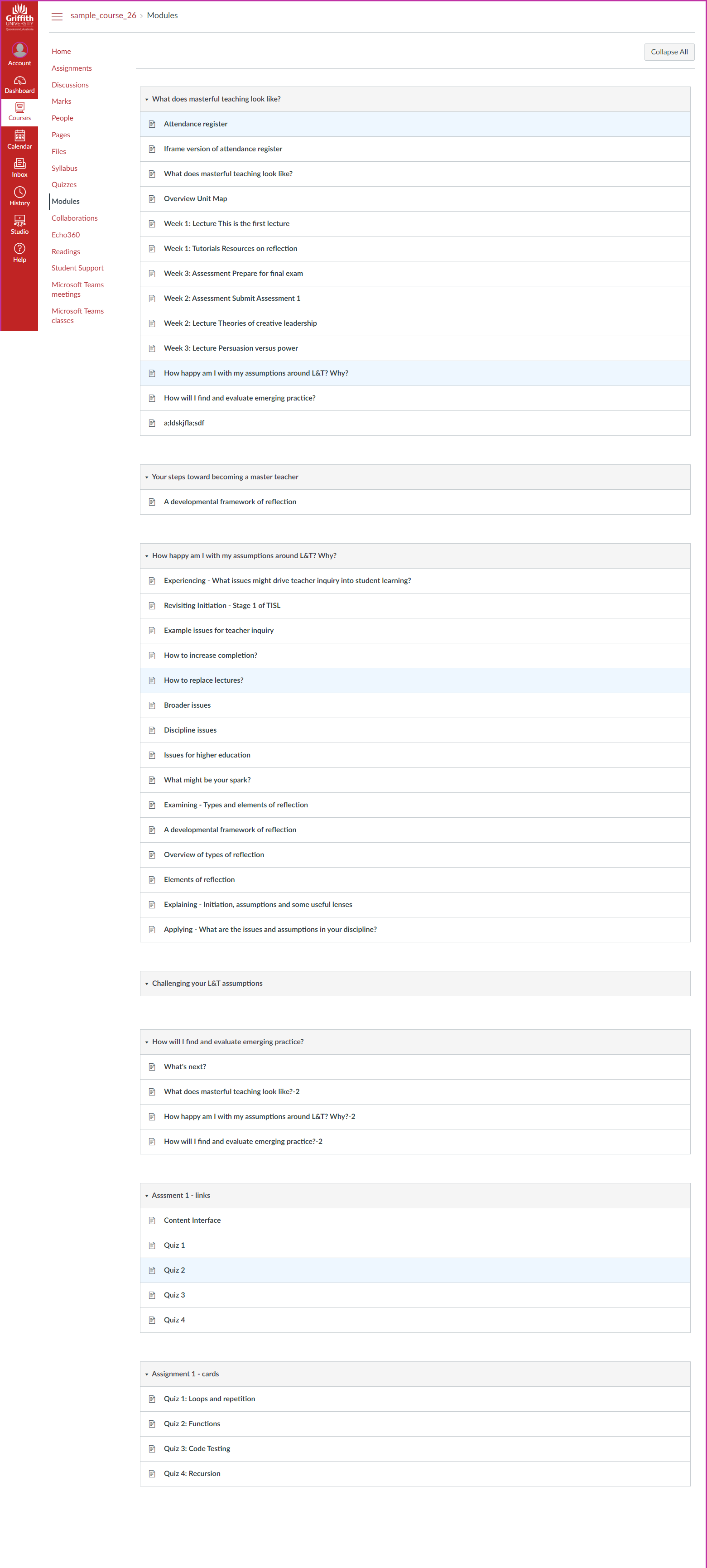

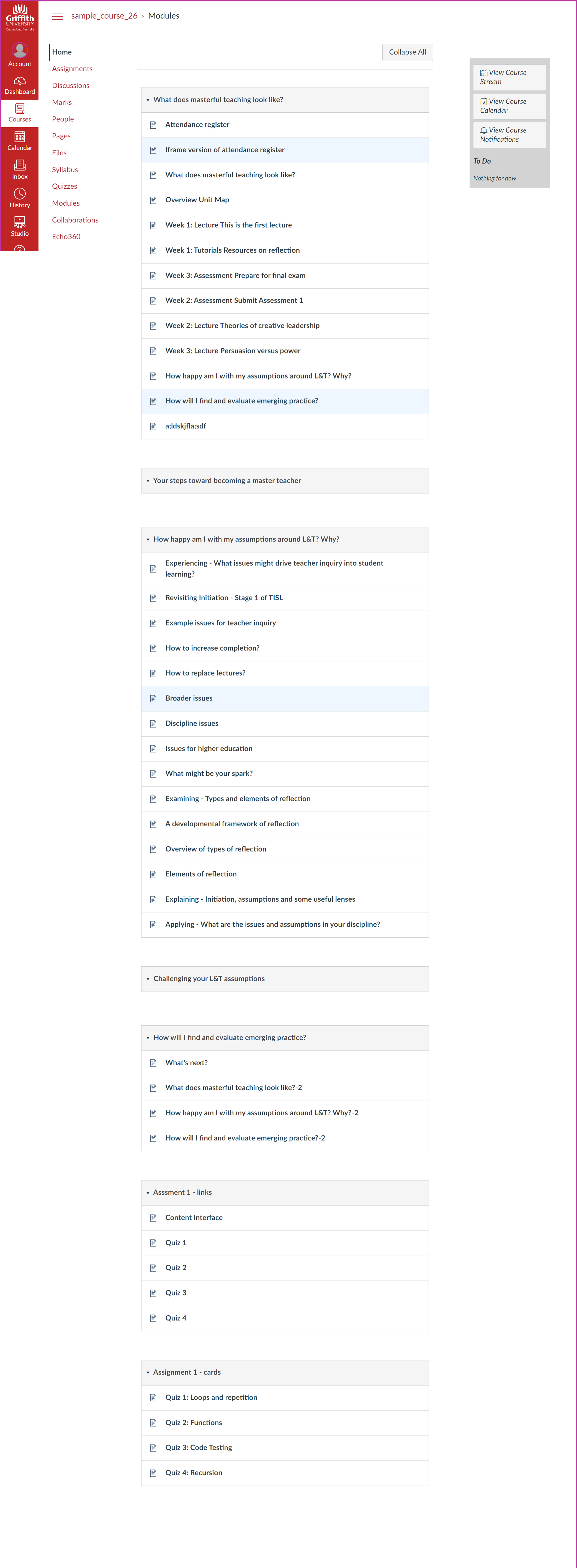

In response to the adoption of a trimester academic calendar, Griffith University encourages the adoption of a modular approach to course design. It is recommended that course profiles use modules to group and describe the teaching and learning activities. Subsequently, it has become common practice for this modular structure to be used within the course site using the Blackboard Learn content area functionality. To do this well, is not straight forward. Blackboard Learn has several functional limitations in legibility, design consistency, content arrangement and content adjustment that make it difficult to achieve quality visual design (Bartuskova, Krejcar, & Soukal, 2015). Usability analysis has also found that the Blackboard content area is inflexible, inefficient to use, and creates confusion for teaching staff regardless of their level of user experience (Kunene & Petrides, 2017). Overcoming these limitations requires levels of technical and design knowledge not typically held by teaching staff. Without this knowledge the resulting designs typically range from purely textual (e.g. the left-hand side of Figure 2) through to exemplars of poor design choices including the likes of blinking text, poor layout, questionable colour choices, and inconsistent design. While specialist design staff can and have been used to provide the necessary design knowledge to implement contextually-appropriate, effective designs, such an approach does not scale. For example, any subsequent modification typically requires the re-engagement of the design staff.

To overcome this challenge the Blackboard Learn user community has developed a collection of related solutions (Abhrahamson & Hillman, 2016; Plaisted & Tkachov, 2011) that use Javascript to package the necessary design knowledge into a form that can be used by teachers. Griffith University has for some time used one of these solutions, the Blackboard Tweaks building block (Plaisted & Tkachov, 2011) developed at the Queensland University of Technology. One of the tweaks offered by this building block – the Themed Course Table – has been widely used by teaching staff to generate a tabular representation of course modules (e.g. the right-hand side of Figure 2). However, experience has shown that the level of knowledge required to maintain and update the Themed Course Table can challenge some teaching staff. For example, re-ordering modules can be difficult for some, and the dates commonly used within the table must be manually added and then modified when copied from one offering to another. Finally, the inherently text-based and tabular design of the Themed Course Table is also increasingly dated. This was an important limitation for the Bachelor of Creative Industries. An alternative was required.

|

|

Figure 2 – Example Blackboard Learn Content Areas: Textual versus Themed Course Table

That alternative would use the same approach as the Themed Course Table to achieve a more appropriate outcome. The approach used by the Themed Course Table, other related examples from the Blackboard community, and the H5P authoring tool (Singh & Scholz, 2017) are contemporary examples of constructive templates (Nanard, Nanard, & Kahn, 1998). Constructive templates arose from the hypermedia discipline to encourage the reuse of design knowledge and have been found to reduce cost and improve consistency, reliability and quality while enabling content experts to author and maintain hypermedia systems (Nanard et al., 1998). Constructive templates encapsulate a specific collection of design knowledge required to scaffold the structured provision of necessary data and generate design instances. For example, the Themed Course Table supports the provision of data through the Blackboard content area interface. It then uses design knowledge embedded within the tweak to transform that data into a table. Given these examples and the author’s prior positive experience with the use of constructive templates within digital learning (Jones, 2011), the initial plan for the BCI Course Content area was to replace the Course Theme Table “template” to adopt both a more contemporary visual design, and a forward-oriented view of design for learning. Dimitriadis and Goodyear (2013) argue that design for learning needs to be more forward-oriented and consider what features will be required in each of the lifecycle stages of a learning activity. That is, as the Course Theme Table replacement is being designed, consider what specific features will be required during configuration, orchestration, and reflection and re-design.

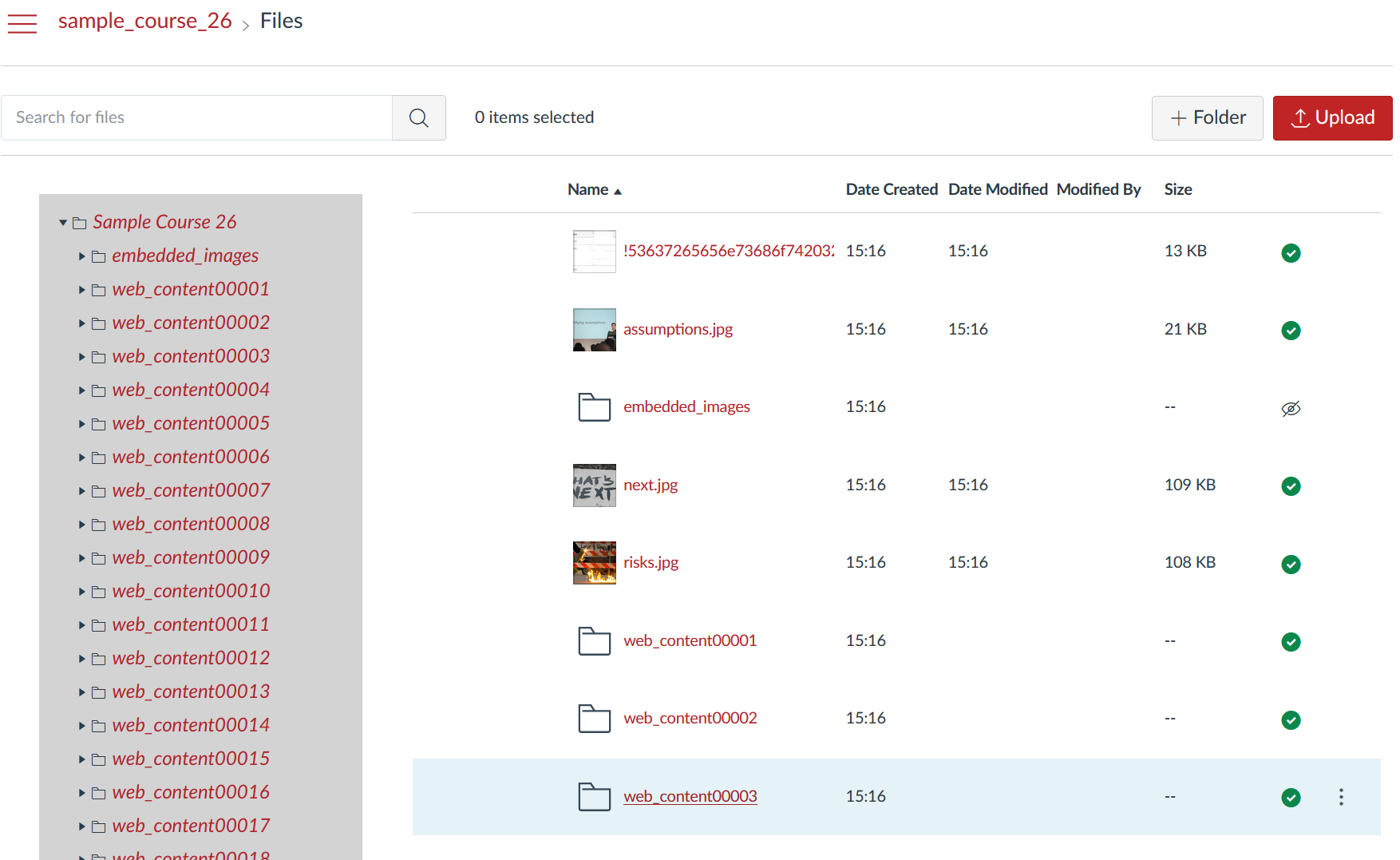

The first step in developing a replacement was to explore contemporary web interface practices for a table replacement. Due to its responsiveness to different devices, highly visual presentation, and widespread use amongst Internet and social media services, a card-based interface was chosen. Based on the metaphor of a paper card, this interface brings together all data for a particular object with an option to add contextual information. Common practice with card-based interfaces is to embed into a card memorable images related to the card content (see Figure 3). Within the context of a course module overview such a practice has the potential to positively impact student cognition, emotions, interest, and motivation (Leutner, 2014; Mayer, 2017). A practical advantage of card-based interfaces is that its widespread use means there are numerous widely available resources to aid implementation. This was especially important to the BCI project team, as it did not have significant graphical and client-side design knowledge to draw upon.

Next, a prototype was developed to test how effectively a card-based interface would represent a course’s learning modules. An iterative process was used to translate features and existing practice from the Course Theme Table to a card-based interface. Feedback from other design staff influenced the evolution of the prototype. It also highlighted differences of opinion about some of the visual elements such as the size of the cards, the number of cards per row, and the inclusion of the date in the top left-hand corner. Eventually the prototype card interface was shown to the BCI teaching team for input and approval. With approval given, a collection of Javascript and HTML was created to transform a specifically formatted Blackboard content area into a card interface.

Figure 3 shows just two of the six different styles of card-based interface currently supported by the Card Interface. This illustrates a key feature of the original conception of constructive templates – separation of content from presentation (Nanard et al., 1998) – allowing for different representations of the same content. The left-hand image in Figure 3 and the inclusion of dates on some cards illustrates one way the Card Interface supports a forward-oriented approach to design. Initially, the module dates are specified during the configuration of a course site. However, the dates typically only apply to the initial offering of the course and will need to be manually changed for subsequent offerings. To address this the Card Interface knows the trimester weekly dates from the university academic calendar. Dates to be included on the Card Interface can then be provided using the week number (e.g. Week 1, Week 5 etc.). The Card Interface identifies the trimester a course offering belongs to and translates all week numbers into the appropriate calendar dates.

|

|

Figure 3 – Two early visualisations of the Card Interface

Despite being designed for the BCI program, the first use of the Card Interface was not in the BCI program. Instead, in late 2018 a librarian working on a Study Skills site learned of the Card Interface from a colleague. Working without any additional support, the librarian was able to use the Card Interface to represent 28 modules spread over 12 content areas. Implementation of the Card Interface in the BCI courses started by drawing on existing learning module content from course profiles. Google Image Search was used to identify visually striking images that could be associated with each module (e.g. the left-hand side of Figure 3). The Card Interface was also used on the BCI program’s Blackboard site. However, the program site had a broader purpose leading to different design decisions and the adoption of a different style of card-based interface (see the right-hand image in Figure 3).

Anecdotal feedback from BCI staff and students suggest that the initial implementation and use of the Card Interface was positive. In addition, the visual improvements offered by the Card Interface over both the standard Blackboard Content Area and the Course Theme Table tweak led to interest from other courses and programs. As of late July 2019, the Card Interface has been used in over 55 content areas in over 30 Blackboard sites. Adoption has occurred at both the program and individual course level led by exposure within the AEL L&T team or by academics seeing it and wanting it. Widespread use has generated different requirements leading to creative uses of the Card Interface (e.g. the use of animated GIFs as card images) and the addition of new functionality (e.g. the ability to embed a video, instead of an image). Requirements from another strategic project led to a customisation of the Card Interface to provide an overview of assessment items, rather than modules.

With its adoption in multiple courses and use for different purposes the Card Interface appears to have successfully encapsulated a collection of design knowledge into a form that can be readily adopted and adapted. Use of that knowledge has improved the resulting design. Contributing factors to this success include: building on existing practice; providing advantages above and beyond existing practice; and, the capability for both teaching and support staff to rapidly customise the Card Interface. Further work is required to gain greater and more objective insight into the impact of the Card Interface on the student experience and outcomes of learning and teaching.

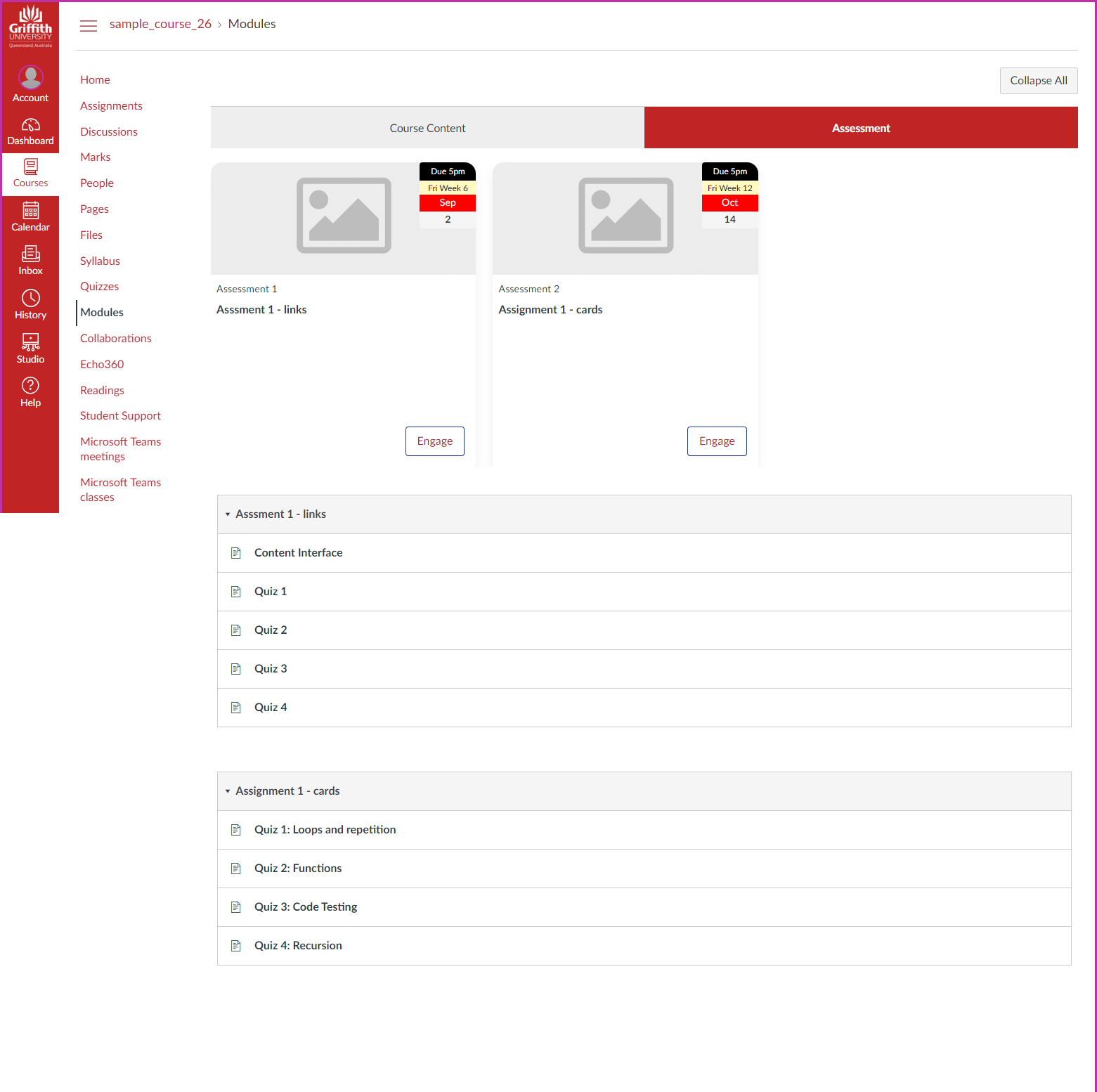

Content Interface (artefact 2, ADR stages 1-3)

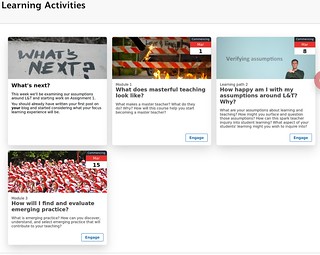

The Card Interface provides a visual overview of course modules. The next challenge for the BCI project was the design, implementation and support of the learning activities and resources that form the content of those course modules. A task that is inherently more creative, important and typically involves significantly more content. Also, a task that must be completed using the same, problematic Blackboard interface. This requirement is known to encourage teaching staff to avoid the interface by using offline documents and slides (Bartuskova et al., 2015). This is despite evidence that failing to leverage affordances of the online environment can create a disengaging student experience (Stone & O’Shea, 2019) and that course content is a significant influence on students’ perceptions of course quality (Peltier, Schibrowsky, & Drago, 2007). Adding to the difficulty, the BCI teaching staff either had limited, none, or little recent experience with Blackboard. In the case of contracted staff, they did not have access to Blackboard. This raised the question of how to support the design, implementation and re-design of effective modular, online learning resources and activities for the BCI?

Observation of, and experience with, the Blackboard interface identified three main issues. First, staff did not know how or have access to the Blackboard content interface. Second, the Blackboard authoring interface provides limited authoring functionality. For example, beyond issues identified in the literature (Bartuskova et al., 2015; Kunene & Petrides, 2017) there is no support for standard authoring functionality such as grammar checking, reference management, commenting, and version control. Lastly, once the content is placed within Blackboard the user interface is limited and quite dated. On the plus side, the Blackboard interface does provide the ability to integrate a variety of different activities such as discussion forums, quizzes etc. The intent was to address the issues while at the same time retaining the ability to use the Blackboard activities.

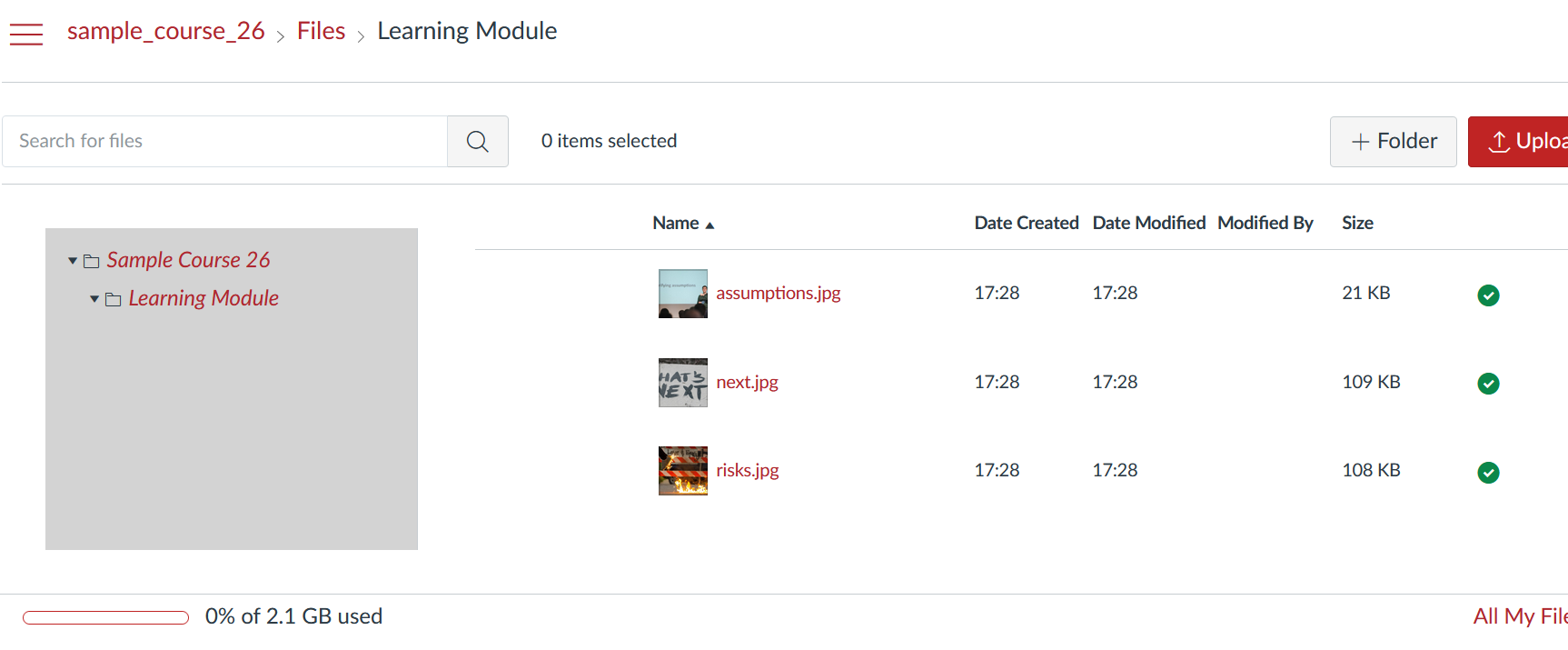

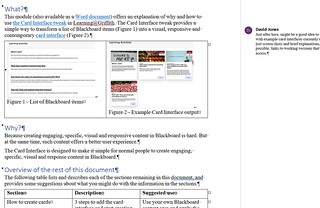

For better or worse, the most common content creation tool for most University staff is Microsoft Word. Anecdotal observation suggests that many staff have adopted the practice of drafting content in Word before copying and pasting it into Blackboard. The Content Interface is designed to transform Word documents into good quality online learning activities and resources (see Figure 4). This is done by using an open source converter to semantically transform Word to HTML that is then copied and pasted into Blackboard. A collection of design knowledge embedded into Javascript then transforms the HTML in several ways. Semantic elements such as activities and readings are visually transformed. All external web links are modified to open in a new tab to avoid a common Blackboard error. The document is transformed into an accordion interface with vertical list of headings that be clicked on to display associated content. This progressive reveal: allows readers to get an overall picture of the module before focusing on the details; provides greater control over how they engage with the content; and is particularly useful on mobile platforms (Budiu, 2015; Loranger, 2014).

|

|

Figure 4 – Example Module as a Word document and in the Content Interface in Blackboard

To date, the Content Interface has been used to develop over 75 modules in 13 different Blackboard sites, most of these within the seven BCI courses. Experience using the still incomplete Content Interface suggests that there are significant advantages. For example, Library staff have adopted it to create research skills modules that are used in multiple course sites. Experience in the BCI shows that sharing documents through OneDrive and using comments and track changes enables the Word documents to become boundary objects helping the course development team co-create the module learning activities and resources. Where staff are comfortable with Word as an authoring environment, the authoring process is more efficient. The resulting accordion interface offers an improvement over the standard Blackboard interface. However, creating documents with Word is not without its challenges, especially the use of Word styles and templates. Also, the extra steps required can be perceived as problematic when minor edits need to be made, and when direct editing within Blackboard is perceived to be easier and quicker, especially for time-poor teaching staff. Better integration between Blackboard and OneDrive will help. More advantage is possible when the Content Interface is further contextually customized to offer forward-oriented functionality specific to the module learning design.

Initial Design Principles (ADR stage 4)

This section engages with the final stage of the ADR process – formalisation of learning – to produce design principles that help provide actionable insight for practitioners. The following six design principles help guide the development of Contextually-Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA) that help to sustainably and at scale share and reuse the design knowledge necessary for effective design for digital learning. The design principles are grouped using the three components of the CASA acronym.

Contextually-Appropriate

1. A CASA should address a specific contextual need within a specific activity

system. The highest quality learning and teaching involves the development of appropriate context-specific approaches (Mishra & Koehler, 2006). A CASA should not be implemented at an institutional level. Such top-down projects are unable to pay enough attention to contextually specific needs as they aim for a solution that works in all contexts. Instead, a CASA should be designed in response to a specific need arising in a course or a small group of related courses. Following Ellis & Goodyear (2019) the focus in designing a CASA should not be the needs of individual students, but instead on the whole activity system. That is, consideration should be given to the complex assemblage of learners, teachers, content, pedagogy, technology, organisational structures and the physical environment with an emphasis on encouraging students to successfully engage in intended learning activities. For example, both the Card and Content Interfaces arose from working with a group of seven courses in the BCI program as the result of two separate, but related, needs. While the issues addressed by these CASA apply to many courses, the ability to develop and test solutions at a small scale was beneficial. Rather than a focus primarily on individual learners, the solutions were heavily influenced by an analysis of the available tools (e.g. Blackboard Tweaks, Office365), practices (e.g. modularisation and learning activities described in course profiles), and other components of the activity systems.

2. CASA should be built using and result in generative technologies. To maximise and maintain contextual appropriateness, a CASA must be able to be designed and redesigned as easily as possible. Zittrain (2008) labels technologies as generative or sterile. Generative technologies have a “capacity to produce unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences” (Zittrain, 2008, p. 70). Sterile technologies prevent this. Generative technologies enable convivial systems where people can be “actively engaged in generating creative extensions to the artefacts given to them” (Fischer & Girgensohn, 1990, p. 183). It is the end-user modifiability of generative technology that is crucial to knowledge-based design environments and enables response to unanticipated, contextual requirements (Fischer & Girgensohn, 1990). Implementing CASA using generative technologies allows easy design for specific contexts. Ensuring that CASA are implemented as generative technologies enables easy redesign for other contexts. Generativity, like other technological affordances, arises from the relationship between the technology and the people using the technology. Not only is it necessary to use technology that is easier to modify, it is necessary to be able to draw upon appropriate technological skills. This could mean having people with those technological skills available to educational design teams. It could also mean having a network of intra- and inter-institutional CASA users and developers collaboratively sharing CASA and the knowledge required for use and development; like that available in the H5P community (Singh & Scholz, 2017).

For example, development of the Card and Content Interfaces was only possible due to Blackboard Learn supporting the embedding of Javascript. The value of this generative capability is evident through the numerous projects (Abhrahamson & Hillman, 2016; Plaisted & Tkachov, 2011) from the Blackboard community that leverage this capability; a capability that has been removed in Blackboard’s next version LMS, Ultra. The use of Office365 by the Content Interface illustrates the rise of digital platforms that are generative and raise questions that challenge how innovation through digital technologies are enabled and managed (Yoo, Boland, Lyytinen, & Majchrzak, 2012). Using the generative jQuery library to implement the Content Interface’s accordion enables modification of the accordion look and feel through use of jQuery’s theme roller and library of existing themes. The separation of content from presentation in the Card Interface has enabled at least six redesigns for different purposes. This work was possible because the BCI development team had ready access to the necessary technological skills and was able to draw upon a wide collection of open source software and online support.

3. CASA development should be strategically aligned and supported. Services to support design for learning within Australian universities are limited and insufficient for the demand (Bennett et al., 2017). Services capable of supporting the development of CASA are likely to be more limited. Hence appropriate decisions need to be made about how and what CASA are designed, re-designed and supported. Resources used to develop CASA are best allocated in line with institutional strategic projects. CASA development should proceed with consideration to the “manageably small set of particularly valued activity systems” (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019, p. 188) within the institution and be undertaken with institutionally approved and supported generative technologies. For example, the Card and Content Interfaces arose from an AEL strategic project. Both interfaces were focused on providing contextually-appropriate customization and support for the institutionally important activity system of creating modular learning activities and resources. Where possible these example CASA have used institutionally approved digital technologies (e.g. OneDrive and Blackboard). The sterile nature of existing institutional infrastructure has made it necessary to use more generative technologies (e.g. Amazon Web Services) that are neither officially approved or supported. However, the approach used does build upon an approach from an existing institutional approved technology – Blackboard Tweaks (Plaisted & Tkachov, 2011).

Scaffolding

4. CASA should package appropriate design knowledge to enable (re-)use by teachers and students. Drawing on ideas from constructive templates (Nanard et al., 1998), CASA should package the diverse design knowledge required to respond to a contextually-appropriate need in a way that this design knowledge can be easily reused in different instances. CASA enable the sustainable reuse of contextually applied design knowledge in learning activity systems and subsequently reduce cost and improve quality and consistency. For example, the Card Interface combines the knowledge from web design and multimedia learning research (Leutner, 2014; Mayer, 2017) in a way that has allowed teaching staff to generate a visual overview of the modules in numerous course sites. The Content Interface combines existing knowledge of the Microsoft

Word ecosystem with web design knowledge to improve the design, use and revision of modular content.

5. CASA should actively support a forward-oriented approach to design for learning.

To “thrive outside of the protective niches of project-based innovation” (Dimitriadis & Goodyear, 2013, p. 1) the design of a CASA must not focus only on initial implementation. Instead, CASA design must explicitly consider and include functionality to support the configuration, orchestration, and reflection and re-design of the CASA. For example, the Card Interface leverages contextual knowledge to enable dates to be specified independent of the calendar to automate re-design for subsequent course offerings. As CASA tend to embody a learning design, it should be possible to improve each CASA’s support for orchestration by implementing checkpoint and process analytics (Lockyer, Heathcote, & Dawson, 2013) specific to the CASA’s embedded learning design.

Assemblages

6. CASA are conceptualised and treated as contextual assemblages. Like all technologies, CASA are assemblies of other technologies (Arthur, 2009) where technologies are understood to include techniques such as organisational processes and pedagogies, as well as hardware and software. But a contextual assemblage is more than just technology. It includes consideration of and connections with the policies, practices, funding, literacies and discourse across levels from societal and down through sector, organisational, personal, individual, formal and informal. These are elements that make up the mess and nuance of the context, where the practice of educational technology gets complex (Cottom, 2019). A CASA must be generative in order to be designed and re-designed to respond to this contextual complexity. A CASA needs to be inherently heterogeneous, ephemeral, local, and emergent. A need that is opposed and ill-suited to the dominant rational system view underpinning common digital learning practice which sees technologies as planned, structured, consistent, deterministic, and systematic. Instead, connecting back to design principle one, CASA should be designed in recognition of and as the importance and complex intertwining of the human, social and organisational elements in any attempt to use digital technologies. It should play down the usefulness of distinctions between developer and user, or pedagogy and technology. For example, the Card Interface does not use the Lego approach to assembly that informs the Next Generation Digital Learning Environment (NGDLE) (Brown, Dehoney, & Millichap, 2015) and underpins technologies such as the Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) standard. Instead of combining clearly distinct blocks with clearly defined connectors the Card and Content Interface is intertwined with and modifies the Blackboard user interface to connect with the specifics of context. Suggesting that the Lego approach is useful, perhaps even necessary, but not sufficient.

Conclusions, Implications, and Further Work

Universities are faced with the strategically important question of how to sustainably and at scale leverage the knowledge required for effective design for digital learning. The early stages of an Action Design Research (ADR) process has been used to formulate one potential answer in the form of six design principles encapsulated in the idea of Context-Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA). To date, the ADR process has resulted in the development and use of two prototype CASA within a suite of 7 courses and within 6 months their subsequent adoption in another 24 courses. CASA draw on the idea of constructive templates to capture diverse design knowledge in a form that enables use of that knowledge by teachers and students to effectively address contextually specific needs. By adopting a forward-oriented view of design for learning CASA offer functionality to support configuration, orchestration, and reflection and re-design in order to encourage on-going use beyond the protected project niche of initial implementation. The use of generative technologies and an assemblage perspective enables CASA development to be driven by and re-designed to fit the specific needs of different activity systems and contexts. Such work will be most effective when it is strategically aligned and supported with the aim of supporting and refining institutionally valued activity systems.

Use of the Card and Content Interfaces within and beyond the original project suggest that these CASA have successfully encapsulated the necessary design knowledge to address shortcomings with current practice and had a positive impact on the quality of the digital learning environment. But it’s early days. These CASA can be improved by more completely following the CASA design principles. For example, the Content Interface currently offers only generic support for module design. Significantly greater benefits would arise from customising the Content Interface to support specific learning designs and provide contextually appropriate forward-oriented functionality. More experience is needed to provide insight into how this can be done effectively. Further work is required to establish if, how and what impact the use of CASA has on the quality of the learning environment and the experience and outcomes of both learning and teaching. Further work could also explore the questions raised by the CASA design principles about existing digital learning practice. The generative principle raises questions about whether moves away from leveraging the generativity of web technology – such the design of Blackboard Ultra and the increasing focus on mobile apps – will make it more difficult to integrate contextually specific design knowledge? Do reported difficulties accessing student engagement data with H5P activities (Singh & Scholz, 2017) suggest that the H5P community could fruitfully pay more attention to supporting a forward-oriented design approach? Does the assemblage principal point to potential limitations with some conceptualisations and implementation of next generation of digital learning environments?

References

Abhrahamson, A., & Hillman, D. (2016). Cutomize Learn with CSS and Javascript injection. Presented at the BBWorld 16, Las Vegas, NV. Retrieved from https://community.blackboard.com/docs/DOC-2103

Alhadad, S. S. J., Thompson, K., Knight, S., Lewis, M., & Lodge, J. M. (2018). Analytics-enabled Teaching As Design: Reconceptualisation and Call for Research. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, 427–435.

Arthur, W. B. (2009). The Nature of Technology: what it is and how it evolves. New York, USA: Free Press.

Bartuskova, A., Krejcar, O., & Soukal, I. (2015). Framework of Design Requirements for E-learning Applied on Blackboard Learning System. In M. Núñez, N. T. Nguyen, D. Camacho, & B. Trawiński (Eds.), Computational Collective Intelligence (pp. 471–480). Springer International Publishing.

Bennett, S., Agostinho, S., & Lockyer, L. (2017). The process of designing for learning: understanding university teachers’ design work. Educational Technology Research & Development, 65(1), 125–145.

Bennett, S., Lockyer, L., & Agostinho, S. (2018). Towards sustainable technology-enhanced innovation in higher education: Advancing learning design by understanding and supporting teacher design practice. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 1014–1026.

Bezuidenhout, A. (2018). Analysing the Importance-Competence Gap of Distance Educators with the Increased Utilisation of Online Learning Strategies in a Developing World Context. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(3), 263–281.

Brown, M., Dehoney, J., & Millichap, N. (2015). The Next Generation Digital Learning Environment: A

Report on Research (p. 11). Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE.

Budiu, R. (2015). Accordions on Mobile. Retrieved July 18, 2019, from Nielsen Norman Group website: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/mobile-accordions/

Cottom, T. M. (2019). Rethinking the Context of Edtech. EDUCAUSE Review, 54(3). Retrieved from

https://er.educause.edu/articles/2019/8/rethinking-the-context-of-edtech

Dahlstrom, E. (2015). Educational Technology and Faculty Development in Higher Education. Retrieved from ECAR website: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2015/6/educational-technology-and-faculty-development-in-higher-education

Dekkers, J., & Andrews, T. (2000). A meta-analysis of flexible delivery in selected Australian tertiary institutions: How flexible is flexible delivery? In L. Richardson & J. Lidstone, (Eds.), Proceedings of

ASET-HERDSA 2000 Conference, (pp. 172-182)

Dimitriadis, Y., & Goodyear, P. (2013). Forward-oriented design for learning: illustrating the approach. Research in Learning Technology, 21, 1–13.

Ellis, R. A., & Goodyear, P. (2019). The Education Ecology of Universities: Integrating Learning,

Strategy and the Academy. Routledge.

Fischer, G., & Girgensohn, A. (1990). End-user Modifiability in Design Environments. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 183–192.

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1344

Goodyear, P. (2015). Teaching As Design. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 2, 27–59.

Goodyear, P., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2013). In medias res: reframing design for learning. Research in

Learning Technology, 21, 1–13.

Gregory, M. S. J., & Lodge, J. M. (2015). Academic workload: the silent barrier to the implementation of technology-enhanced learning strategies in higher education. Distance Education, 36(2), 210–230.

Jones, D. (2011). An Information Systems Design Theory for E-learning (PhD, Australian National University). Retrieved from https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/8370

Kunene, K. N., & Petrides, L. (2017). Mind the LMS Content Producer: Blackboard usability for improved productivity and user satisfaction. Information Systems, 14.

Leutner, D. (2014). Motivation and emotion as mediators in multimedia learning. Learning and

Instruction, 29, 174–175.

Lockyer, L., Heathcote, E., & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing Pedagogical Action: Aligning Learning Analytics With Learning Design. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1439–1459.

Loranger, H. (2014). Accordions for Complex Website Content on Desktops. Retrieved July 18, 2019, from Nielsen Norman Group website: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/accordions-complex-content/

Mathes, J. (2019). Global quality in online, open, flexible and technology enhanced education: An analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Retrieved from International Council for Open and Distance Education website:

https://www.icde.org/knowledge-hub/report-global-quality-in-online-education

Mayer, R. E. (2017). Using multimedia for e-learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

33(5), 403–423.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Mor, Y., Craft, B., & Maina, M. (2015). Introduction – Learning Design: Definitions, Current Issues and Grand Challenges. In M. Maina, B. Craft, & Y. Mor (Eds.), The Art & Science of Learning Design (pp. ix–xxvi). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Nanard, M., Nanard, J., & Kahn, P. (1998). Pushing Reuse in Hypermedia Design: Golden Rules, Design

Patterns and Constructive Templates. 11–20. ACM.

Peltier, J. W., Schibrowsky, J. A., & Drago, W. (2007). The Interdependence of the Factors Influencing the Perceived Quality of the Online Learning Experience: A Causal Model. Journal of Marketing Education; Boulder, 29(2), 140–153.

Plaisted, T., & Tkachov, N. (2011). Blackboard Tweaks: Tools for Academics, Designers and Programmers. Retrieved July 2, 2019, from http://tweaks.github.io/Tweaks/index.html

Roberts, J. (2018). Future and changing roles of staff in distance education: A study to identify training and professional development needs. Distance Education, 39(1), 37–53.

Sein, M. K., Henfridsson, O., Purao, S., & Rossi, M. (2011). Action Design Research. MIS Quarterly,

35(1), 37–56.

Singh, S., & Scholz, K. (2017). Using an e-authoring tool (H5P) to support blended learning: Librarians’ experience. In H. Partridge, K. Davis, & J. Thomas (Eds.), Me, Us, IT! Proceedings ASCILITE2017: 34th International Conference on Innovation, Practice and Research in the Use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education (pp. 158–162).

Stone, C., & O’Shea, S. (2019). Older, online and first: Recommendations for retention and success.

Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3913

Yoo, Y., Boland, R. J., Lyytinen, K., & Majchrzak, A. (2012). Organizing for Innovation in the Digitized World. Organization Science, 23(5), 1398–1408.

Zittrain, J. (2008). The Future of the Internet–And How to Stop It. Yale University Press.