When it comes to research I’ve been a bit of failure, especially when measured against some of the more recent strategic and managerial expectations. Where are those quartile 1 journal articles? Isn’t your h-index showing a downward trajectory?

The concern generated by these quantitative indicators not only motivated the following ideas for a broad research topic, but also is one of the issues to explore within the topic. The following outlines early attempts to identify a broader research topics that is relevant enough for current sector and institutional concerns; provides sufficient space for interesting research and contribution; aligns nicely (from one perspective) with my day job; and, will likely provide a good platform for a program of collaborative research.

The following:

- explains the broad idea for research topic within the literature; and,

- describes the work we’ve done so far including two related examples of the initial analytics/indicators we’ve explored.

The aim here is to be generative. We want to do something that generates mutually beneficial collaborations with others. If you’re interested, let us know.

Research topic

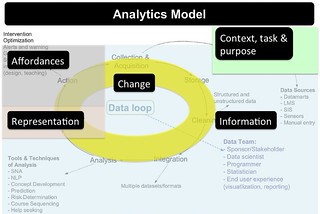

As currently defined the research topic is focused around the design and critical evaluation of the use and value of a learning analytics platform to support meso-level practitioners in higher education to engage with quality indicators of learning and teaching.

Amongst the various aims, are an intent to:

- Figure out how to design and implement an analytics platform that is useful for meso-level practitioners.

- Develop design principles for that platform informed by the analytics research, but also ideas from reproducible research and other sources.

- Use and encourage the use by others of the platform to:

- explore what value (if any) can be extracted from a range of different quality indicators;

- design interventions that can help improve L&T; and,

- to enable for a broader range of research – especially critical research – around the use of quality indicators and learning analytics for learning and teaching.

Quality Indicators

The managerial turn in higher education has increased the need for and use of various indicators of quality, especially numeric indicators (e.g. the number of Q1 journal articles published, or not). Kinash et al (2015) state the quantifiable performance indicators are important to universities because they provide “explicit descriptions of evidence against which quality is measured” (p. 410). Chalmers (2008) offers the following synthesized definition of performance indicators

measures which give information and statistics context; permitting comparisons between fields, over time and with commonly accepted standards. They provide information about the degree to which teaching and learning quality objectives are being met within the higher education sector and institutions. (p. 10)

However, the generation and use of these indicators is not without issues.

There is also a problem with a tendency to rely on quantitative indicators. Quantitative indicators provide insight into “how much or how many, but say little about quality” (Chalmers & Gardiner, 2015, p. 84). Ferguson and Clow (2017) – writing in the context of learning analytics – argue the good quality qualitative research needs to support good-quality quantitative research because “we cannot understand the data unless we understand the context”. Similarly, Kustra et al (2014) suggest that examining the quality of teaching requires significant qualitative indicators to “provide deeper interpretation and understanding of the measured variable”. Qualitative indicators are used by Universities to measure performance in terms of processes and outcomes,however, “because they are more difficult to measure and often produce tentative results, are used less frequently” (Chalmers & Gardiner, 2015, p. 84)

Taking a broader perspective there are problems such as Goodhart’s law and performativity. As restated by Strathern (1997), Goodhart’s Law is ‘When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure’ (p. 308) Elton (2004) describes Goodhart’s Law as “a special case of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle in Sociology, which states that any observation of a social system affects the system both before and after the observation, and with unintended and often deleterious consequences” (p. 121). When used for control and comparison purposes (e.g league tables) indicators “distort what is measured, influence practice towards what is being measured and cause unmeasured parts to get neglected” (Elton, 2004, p. 121).

And then there’s the perception that quality indicators and potentially this whole research project becomes an unquestioning part of part of performativity and all of the issues that generates. Ball (2003) outlines the issues and influence of the performative turn in institutions. He describes performativity as

a technology, a culture and a mode of regulation that employs judgements, comparisons and displays as means of incentive, control, attrition and change ^ based on rewards and sanctions (both material and symbolic). The performances (of individual subjects or organizations) serve as measures of productivity or output, or displays of ‘quality’, or ‘moments’ of promotion or inspection (Ball, 2003, p. 216)

All of the above (and I expect much more) all point to there being interesting and challenging questions to explore and answer around quality indicators and beyond. I do hope that any research we do around this topic engages with the necessary critical approach to this research. As I re-read this post now I can’t help but see echoes of a previous discussion Leigh and I have had around inside out, outside in, or both. This approach is currently framed as an inside out approach. An approach where those inside the “system” are aware of the constraints and work to address those. The question remains whether this is possible.

Learning analytics

Siemens and Long (2011) define LA as “the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimizing learning and the environments in which it occurs” (p. 34). The dominant application of learning analytics has focused on “predicting student learning success and providing proactive feedback” (Gasevic, Dawson and Siemens, 2015), often driven by an interest in increasing student retention and success. Colvin et al (2016) found two distinct trajectories of activity in learning analytics within Australian higher education. The first were ultimately motivated by measurement and retention implemented specific retention related learning analytics programs. The second saw retention as a consequence of the broader learning and teaching experience and “viewed learning analytics as a process to bring understanding to learning and teaching practices” (Colvin et al, 2016, p. 2).

Personally, I’m a fan of the second trajectory and see supporting that trajectory as a major aim for this project.

Not all that surprisingly, learning analytics has been applied to the question of quality indicators. Dawson and McWilliam (2008) explored the use of “academic analytics” to

address the need for higher education institutions (HEIs) to develop and adopt scalable and automated measures of learning and teaching performance in order to evaluate the student learning experience (p. 1)

Their findings included (emphasis added):

- “LMS data can be used to identify significant differences in pedagogical approaches adopted at school and faculty levels”

- “provided key information for senior management for identifying levels of ICT adoption across the institution, ascertaining the extent to which teaching approaches reflect the strategic institutional priorities and thereby prioritise the allocation of staff development resources”

- refining the analysis can identify “further specific exemplars of online teaching” and subsequently identify “‘hotspots’ of student learning engagement”; “provide lead indicators of student online community and satisfaction”; and, identify successful teaching practices “for the purposes of staff development activities and peer mentoring”

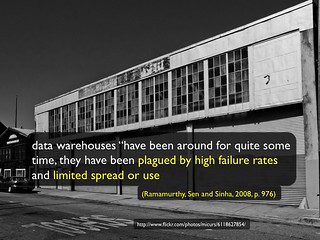

Macfadyen and Dawson (2012) provide examples of how learning analytics can reveal data that offer “benchmarks by which the institution can measure its LMS integration both over time, and against comparable organizations” (p. 157). However, the availability of such data does not ensure use in decision making. Macfadyen and Dawson (2012) also report that the availability of patterns generated by learning analytics did not generate critical debate and consideration of the implications of such data by the responsible organisational committee and thus apparently failed to influence institutional decision-making.

A bit more surprising, however, is that in my experience there doesn’t appear to have been a concerted effort to leverage learning analytics for these purposes. Perhaps this is related to findings from Colvin et al (2016) that even with all the attention given to learning analytics there continues to be: a lack of institutional exemplars; limited resources to guide implementation; and perceived challenges in how to effectively scale learning analytics across an institution. There remains little evidence that learning analytics has been helpful in closing the loop between research and practice, and made an impact on university-wide practice (Rogers et al, 2016).

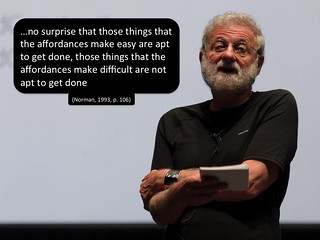

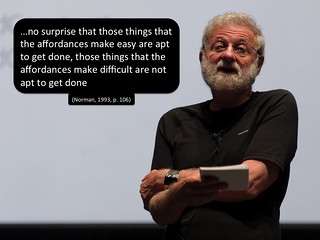

Even if analytics is used, there are other questions such as the role of theory and context. Gasevic et al (2015) argue that while counting clicks may provide indicators of tool use it is unlikely to reveal insights of value for practice or the development of theory. If learning analytics is to achieve an a lasting impact on student learning and teaching practice it will be necessary to draw of appropriate theoretical models (Gasevic et al, 2015). Rogers et al (2016) illustrate how such an approach “supports an ever-deepening ontological engagement that refines our understanding and can inform actionable recommendations that are sensitive to the situated practice of educators” (p. 245). If learning analytics aims to enhance to learning and teaching, it is crucial that it engages with teachers and their dynamic contexts (Sharples et al., 2013). Accounting for course and context specific instructional conditions and learning designs are increasingly seen as imperatives for the use of learning analytics (Gaservic et al, 2015; Lockyer et al, 2013)

There remain many other questions about learning analytics. Many of those questions are shared with the use of quality indicators. There is also the question of how learning analytics can harnessed via means that are sustainable, scale up, and at the same time provide contextually appropriate support. How can the tensions between the need for institutional level quality indicators of learning and teaching, and the inherently contextually specific nature of learning and teaching?

Meso-level practitioners

The limited evidence of impact from learning analytics on learning and teaching practice may simply be a mirror of the broader difficulty that universities have had with other institutional learning technologies. Hannon (2013) explains that when framed as a technology project the implementation of institutional learning technologies “risks achieving technical goals accompanied by social breakdowns or failure, and with minimal effect on teaching and learning practices” (p. 175). Breakdowns that arise, in part, from the established view of enterprise technologies. A view that sees enterprise technologies as unable to be changed, and “instead of optimizing our machines for humanity – or even the benefit of some particular group – we are optimizing humans for machinery” (Rushkoff, 2010, p. 15).

Jones et al (2006) describe the term meso-level to describe the “level that was intermediate between small scale, local interaction, and large-scale policy and institutional procesess” (p. 37). Hannon (2013) describes meso-level practitioners as the “teaching academics, learning technologists, and academic developers” (p. 175) working between the learning and teaching coal-face and the institutional context defined by an institution’s policies and technological systems. These are the people who can see themselves as trying to bridge the gaps between the institutional/technological vision (macro-level) and the practical coal-face realities (micro-level). These are the people who are often required to help “optimise humans for machinery”, but who would generally prefer to do the reverse. Hannon (2013) also observes thateEven though there has been significant growth in the meso-level within contemporary higher education, research has continued to largely focused on the macro or micro levels.

My personal experience suggests that the same can be said about the design and use of learning analytics. Most institutional attempts are focused at either the macro or micro level. The macro level focused largely on large-scale student retention efforts. The micro level focused on the provision of learning analytics dashboards and other tools to teaching staff and students. There has been some stellar work by meso-level practitioners in developing supports for the micro-level (e.g. Liu, Bartimote-Aufflick, Pardo, & Bridgeman, 2017). However, much of this work has been in spite of the affordances and support offered by the macro-level. Not enough of the work, beyond the exceptions already cited, appears to have actively attempted to help optimise the machinery for the humans. In addition, there doesn’t appear to be a great deal of work – beyond the initial work from almost 10 years ago – focused on if and how learning analytics can help meso-level practitioners in the work that they do.

As a result there are sure to be questions to explore about meso-level practitioners, their experience and impact on higher education. Leigh Blackall has recently observed that the growth in meso-level practitioners in the form of “LMS specialists and ed tech support staff” comes with the instruction that they “focus their attentions on a renewed sense of managerial oversight”. Implicating meso-level practitioners in questions related to performativity etc. Leigh also positions these meso-level practitioners as examples of disabling professions. Good pointers to some of the more critical questions to be asked about this type of work.

Can meso-level practitioners break out, or are we doomed to be instruments of performativity? What might it take to break free? How can learning analytics be implemented in a way that allows it to be optimised for the contextually specific needs of the human beings involved, rather than require the humans to be optimised for the machinery? Would such a focus improve the quality of L&T?

What have we done so far?

Initial work has focused on developing an open, traceable, cross-institutional platform for exploring learning analytics. In particular, exploring how recent ideas such as reproducible research and insights from learning analytics might help design a platform that enables meso-level practitioners to break some of the more concerning limitations of current practice.

We’re particularly interested in ideas from Elton (2004) where bottom-up approaches might “be considerably less prone to the undesirable consequences of Goodhart’s Law” (p. 125). A perspective that resonates with our four paths idea for learning analytics. i.e. That it’s more desirable and successful to follow the do-it-with learners and teachers or learner/teacher DIY paths.

The “platform” is seen as an enabler for the rest of the research program. Without a protean technological platform – a platform we’re able to tailor to our requirements – it’s difficult to see how we’d be able to effectively support the deeply contextual nature of learning and teaching or escape broader constraints such as performativity. This also harks back to my disciplinary background as a computer scientist. In particular, the computer scientist as envisioned by Brooks (1996) as a toolsmith whose delight “is to fashion powertools and amplifiers for minds” (p. 64) and who “must partner with those who will use our tools, those whose intelligences we hope to amplify” (p. 64).

First steps

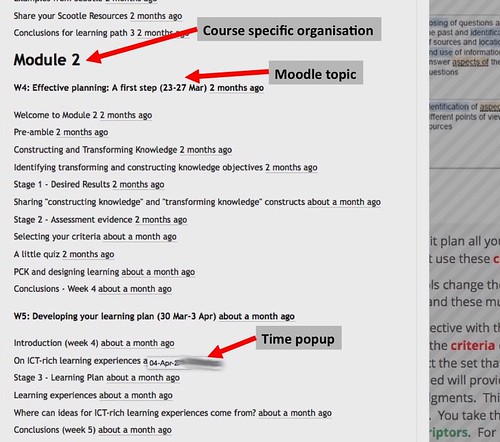

As a first step, we’re revisiting our earlier use of Malikowski, Thompson & Theis (2007) to look at LMS usage (yea, not that exciting, but you have to start somewhere). We’ve developed a set of Python classes that enable the use of the Malikowski et al (2007) LMS research model. That set of classes has been used to develop a collection of Jupyter notebooks that help explore LMS usage in a variety of ways.

The theory is that these technologies (and the use of github to share the code openly) should allow anyone else to perform these same analysis with their LMS/institution. So far, the code is limited to working only with Moodle. However, we have been successful in sharing code between two different installations of Moodle. i.e. one of us can develop some new code, share it via github, and the other can run that code over their data. A small win.

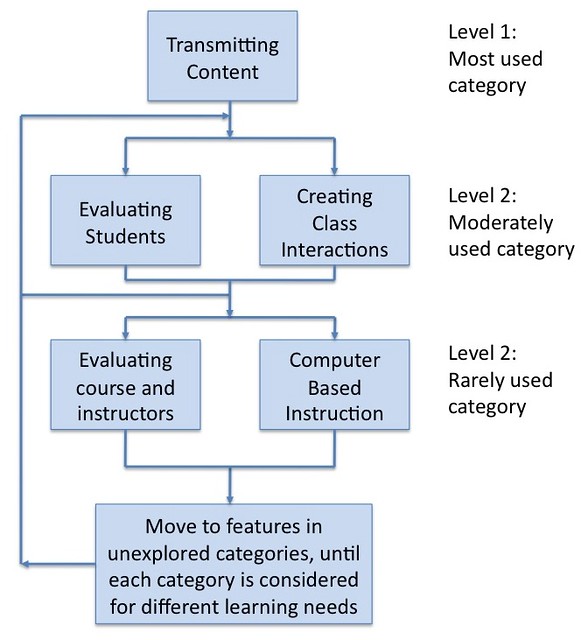

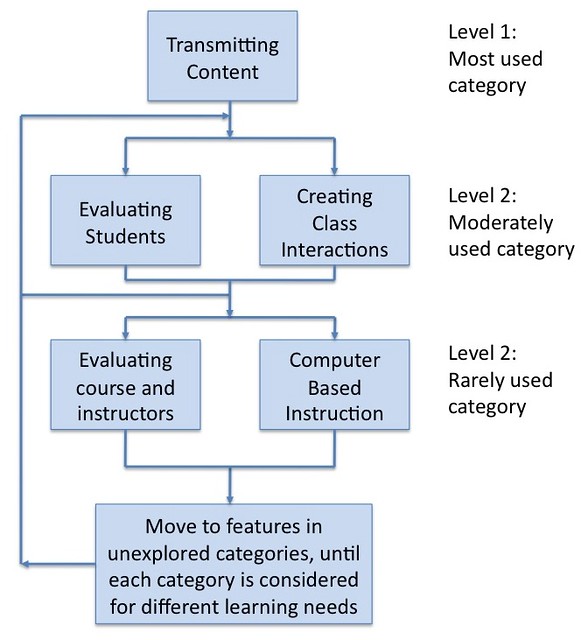

The Malikowski et al (2007) model groups LMS features by the following categories: Content, Communication, Assessment, Evaluation and Computer-Based Instruction. It also suggests that tool use occurs in a certain order and with a certain frequency. The following figure (click on it to see a larger version) is a representation of the Malikowski model.

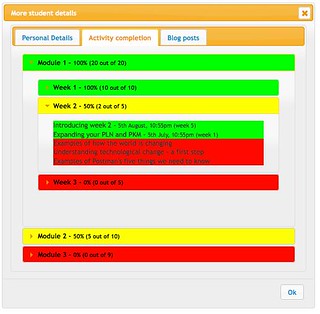

Looking for engagement?

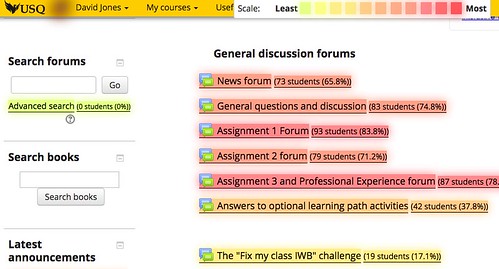

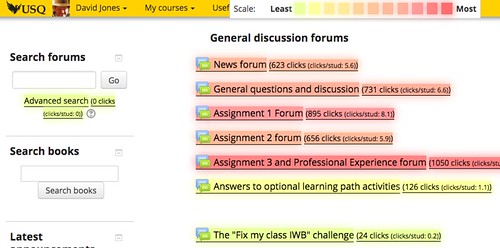

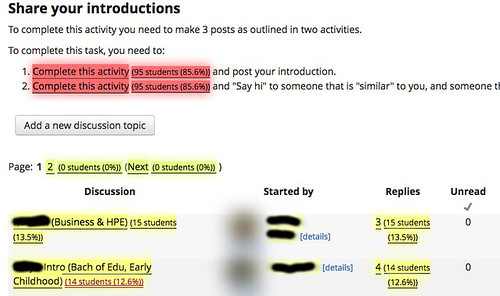

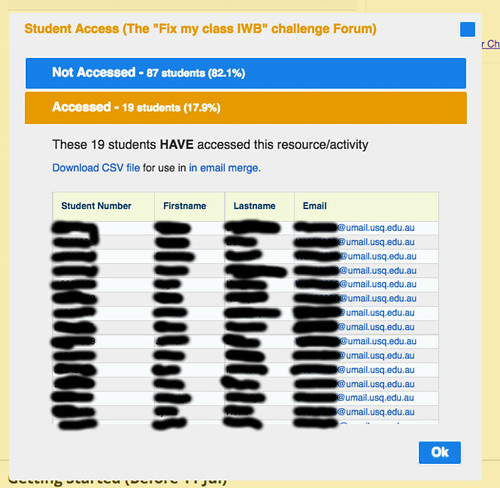

Dawson and McWilliam (2008) suggested that academic analytics could be used to identify “potential “hotspots” of student learning engagement” (p. 1). Assuming that the number of times students click within an LMS course is a somewhat useful proxy for engagement (a big question), then this platform might allow you to:

- Select a collection of courses.

This might be all the courses in a discipline that scored well (or poorly) on some other performance indicator, all courses in a semester, all large first year courses, all courses in a discipline etc.

- Visualise the number of total student clicks within each course clicked on LMS functionality in each of the Malikowski categories.

- Visualise the number of clicks per student within each course in each Malikowski category.

These visualisations might then provide a useful indication of something that is (or isn’t) happening. An indication that would not have been visible otherwise and is worthy of further exploration via other means (e.g. qualitative).

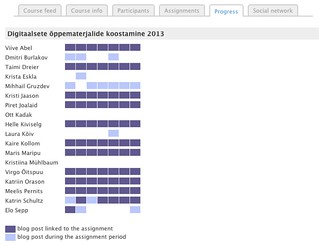

The following two graphs were generated by our platform and are included here to provide a concrete example of the above process. Some features of the platform that the following illustrates

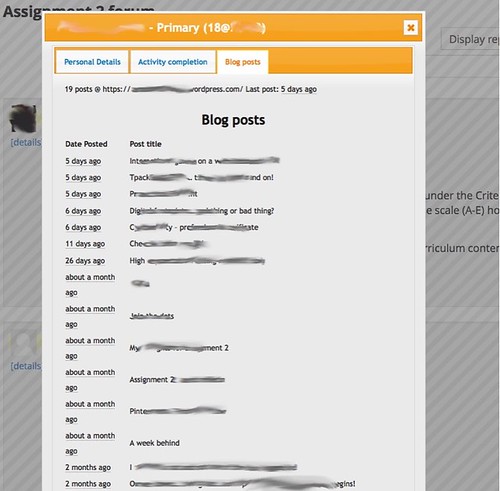

- It generates artefacts (e.g. graphs, figures) that can be easily embedded anywhere on the web (e.g. this blog post). You don’t have to be using out analytics platform to see the artefacts.

- It can anonymise data for external display. For example, courses in the following artefacts have been randomly given people’s names rather than course codes/names.

Number of total student clicks

The first graph shows a group of 7 courses. It shows the number of students enrolled in each course (e.g. the course Michael has n=451) and the bars represent the total number of clicks by enrolled students on the course website. The clicks are grouped according to the Malikowski categories. If you roll your mouse over one of the bars, then you should see displayed the exact number of clicks for each category.

For example, the course Marilyn with 90 students had

- 183,000+ clicks on content resources

- 27,600+ clicks on communication activities

- 5659 clicks on assessment activities

- and 0 for evaluation of CBI

Total number of clicks isn’t all that useful for course comparisons. Normalising to clicks per enrolled student might be useful.

Clicks per student

The following graph uses the same data as above, however, the number of clicks is now divided by the number of enrolled students. A simple change in analysis that highlights differences between courses.

2000+ clicks on content per student certainly raises some questions about the Marilyn course. Whether that number is good, bad, or meaningless would require further exploration.

What’s next?

We’ll keep refining the approach, some likely work could include

- Using different theoretical models to generate indicators.

- Exploring how to effectively supplement the quantitative with qualitative.

- Exploring how engaging with this type of visualisation might be a useful as part of professional learning.

- Exploring if these visualisations can be easily embedded within the LMS, allowing staff and students to see appropriate indicators in the context of use.

- Exploring various relationships between features quantitatively.

For example, is there any correlation between results on student evaluation and Malikowski or other indicators? Correlations between disciplines or course design?

- Combining the Malikowski model with additional analysis to see if it’s possible to identify significant changes in the evolution of LMS usage over time.

e.g. to measure the impact of organisational policies.

- Refine the platform itself.

e.g. can it be modified to support other LMS?

- Working with a variety of people to explore what different questions they might wish to answer with this platform.

- Using the platform to enable specific research project.

And a few more.

Want to play? Let me know. The more the merrier.

References

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

Brooks, F. (1996). The Computer Scientist as Toolsmith II. Communications of the ACM, 39(3), 61–68.

Chalmers, D. (2008). Indicators of university teaching and learning quality.

Chalmers, D., & Gardiner, D. (2015). An evaluation framework for identifying the effectiveness and impact of academic teacher development programmes. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.002

Colvin, C., Wade, A., Dawson, S., Gasevic, D., Buckingham Shum, S., Nelson, K., … Fisher, J. (2016). Student retention and learning analytics : A snapshot of Australian practices and a framework for advancement. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching. Retrieved from http://he-analytics.com/wp-content/uploads/SP13-3249_-Master17Aug2015-web.pdf

Dawson, S., & McWilliam, E. (2008). Investigating the application of IT generated data as an indicators of learning and teaching performance. Queensland University of Technology and the University of British Columbia.

Elton, L. (2004). Goodhart’s Law and Performance Indicators in Higher Education. Evaluation & Research in Education, 18(1–2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790408668312

Ferguson, R., & Clow, D. (2017). Where is the Evidence?: A Call to Action for Learning Analytics. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Learning Analytics & Knowledge Conference (pp. 56–65). New York, NY, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3027385.3027396

Gašević, D., Dawson, S., & Siemens, G. (2015). Let’s not forget: Learning analytics are about learning. TechTrends, 59(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-014-0822-x

Gašević, D., Dawson, S., Rogers, T., & Gasevic, D. (2015). Learning analytics should not promote one size fits all: The effects of instructional conditions in predicating learning success. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.10.002

Hannon, J. (2013). Incommensurate practices: sociomaterial entanglements of learning technology implementation. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(2), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2012.00480.x

Jones, C., Dirckinck‐Holmfeld, L., & Lindström, B. (2006). A relational, indirect, meso-level approach to CSCL design in the next decade. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 1(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-006-6841-7

Kinash, S., Naidu, V., Knight, D., Judd, M.-M., Nair, C. S., Booth, S., … Tulloch, M. (2015). Student feedback: a learning and teaching performance indicator. Quality Assurance in Education, 23(4), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-10-2013-0042

Liu, D. Y.-T., Bartimote-Aufflick, K., Pardo, A., & Bridgeman, A. J. (2017). Data-Driven Personalization of Student Learning Support in Higher Education. In A. Peña-Ayala (Ed.), Learning Analytics: Fundaments, Applications, and Trends (pp. 143–169). Springer International Publishing.

Lockyer, L., Heathcote, E., & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing Pedagogical Action: Aligning Learning Analytics With Learning Design. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1439–1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479367

Macfadyen, L., & Dawson, S. (2012). Numbers Are Not Enough. Why e-Learning Analytics Failed to Inform an Institutional Strategic Plan. Educational Technology & Society, 15(3), 149–163.

Malikowski, S., Thompson, M., & Theis, J. (2007). A model for research into course management systems: bridging technology and learning theory. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 36(2), 149-173.

Rogers, Tim, Dawson, Shane, & Gasevic, Dragan. (2016). Learning Analytics and the Imperative for Theory-Driven Research. In The SAGE Handbook of E-learning Research (2nd ed., pp. 232–250).

Rushkoff, D. (2010). Program or be programmed: Ten commands for a digital age. New York: OR Books.

Sharples, M., Mcandrew, P., Weller, M., Ferguson, R., Fitzgerald, E., & Hirst, T. (2013). Innovating Pedagogy 2013: Open University Innovation Report 2 (No. 9781780079370). Milton Keynes: UK. Retrieved from http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/innovating/

Siemens, G., & Long, P. (2011). Penetrating the Fog: Analytics in Learning and Education. EDUCAUSE Review, 46(5). Retrieved from http://moourl.com/j6a5d

Strathern, M. (1997). “Improving ratings”: audit in the British University system. European Review, 5(3), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1234-981X(199707)5:3<305::AID-EURO184>3.0.CO;2-4