It’s widely accepted that the most important part of learning and teaching is what the student does (Biggs, 2012). The spaces, tools and tasks in and through which students “do stuff” (i.e. learning, or not) are in some way designed by a teacher with subsequent learner adaptation (Goodyear, 2020).

Designing learning spaces, tools and tasks is not easy. Especially when digital technologies are involved. The low digital fluency of teachers is seen as a (for some the) significant challenge (Johnson et al, 2014). Hence the big focus on solutions such as requiring all teachers to have a formal teaching qualification. Formal “certification” programs such as the HEA. Or the focus on running workshops and producing online “how-to” support material. The focus on teacher knowledge tends to ignore the distributed and contextual nature of the knowledge required. It doesn’t just reside in the heads of the teachers but is distributed amongst the other agents (people, technologies, policies etc) in the institutional learning and teaching system (Jones et al, 2015).

When knowledge is distributed, it is also situated and highly contextual. As such, knowing the details of any learning and teaching model or theory has value still has to be translated into the design of learning activities within a specific learning and teaching context. The model’s suggestions needs to be adapted and customised to the specifics of the learning activity, including the specific discipline, the specific digital technologies, the specific institutional policies, the specific student cohort etc. This is hard and I don’t know of any institution that is helping meaningfully and sustainably make this problem easier in contextually and discipline specific ways.

This post will

- Introduce a discipline specific learning activity.

- Describe the learner and teacher experiences of engaging with current common implementations of that learning activity.

- Illustrate how the learner and teacher experience is changed by a more discipline specific approach.

- Explore some of the implications and next steps for this approach.

Watching films – a discipline-specific activity

A key activity for courses such as film analysis, history, direction etc. is watching films. Analysing existing films to see how certain theories and design principles have been leveraged and their impact. A necessary first step in such a learning activity is being able to source and watch the film. In an on-campus learning experience this is probably a face-to-face experience in a scheduled class. In a totally online learning experience this is commonly done via the course web site. Either way the teacher/institution typically organises access to the film and designs some activity around it.

This type of close analysis of a film typically only a part of a handful (or two) of courses at a university. If there’s any institutional support for this activity it is typically a small part of a broader process. e.g. legally (copyright) correct sourcing of films may be part of the library service. But typically, designing this learning activity draws more on the significant capabilities and expertise of the teacher. Not unlike most of the other activities specific to the other disciplines. Typically this appears to work in the face-to-face environment, but what happens when it goes online?

Watching films in an online course – the current solution

The following is a generic description summarising the practice I’ve observed at a couple of different institutions. I imagine it’s fairly typical. I’m sure there are much better examples of current practice. But my hypothesis is that those better examples were dependent upon an individual with a unique combination of knowledge and skills.

The learner experience

Somewhere on the course site the learner will discover that they need to watch a film (or two) this week. This may be via an announcement, a list of films in a course profile or course reading list, or some details in this week’s page on the course site. There will some details about the film (e.g. director, year of production etc.), perhaps a description of how to engage with the film, and there might be access to a digital version of the film.

Since many films are commercial, copyrighted artefacts. Providing digital access to the film is not straight forward. In some cases the institution may be able to provide access. In other cases the learners or teachers may have shared URLs enabling (probably legally dubious and short-lived) access. In other cases the student is left up to their own devices to gain access to the film. With the rise of streaming services this is significantly easier. However, the nature and diversity of the films used in such courses is such that no single streaming service will provide access. Increasing expense for learners. Also, not all such films will be available via streaming services.

Consequently, learners typically expend a fair bit of cognitive effort and time gaining access to films. A cognitive effort expense which may be seen as a part of the necessary and relevant learning for the course. But it may be a cognitive enegy expense that limits what the learner invests in the actual important learning activities involved in understanding and analysing the film. I have heard reports of learners in such courses being frustrated at having to expend this cognitive effort.

The teacher experience

The teacher of such a course faces four broad questions. Answering these questions is not sequential. My answer to question #1 may change depending on the answer to question #2. The four questions are:

- Which films should the students engage with?

- Can I provide access to those films?

- How to point students to those films and what they need to do?

- How well did those films/activities work and what do I need to change for next time?

Answering question #1 draws on the discipline knowledge of the teacher. All the other questions require knowledge that is not (solely) discipline knowledge.

Answering question #2 involves knowledge of copyright law and various institutional systems and processes. that the university’s library. Most provide a service that can legally gain digital access to films. Well, most films. Such a process is typically part of a broader process of providing resources for teaching (e.g. my current institution) which may feed into some sort of formal course reading list. I’ve yet to see such a formal course reading list that is useful for learning and teaching.

Answering question #3 requires pedagogical and technical knowledge to figure where, when and how to embed this information in a course site. It’s the teacher that needs this knowledge. They are provided with generic tools (announcements, discussion boards, and content editing), maybe the formal course reading list, and supported by generic technical and pedagogical advice about how to use the provided tools. None of this is specific to film watching.

Hence answers to question #3 are largely variable. See mention of learner frustration in the previous section. The most common solution I’ve seen is just a description of the films to watch such as the following simple example.

Answering question #4 requires knowledge of learner activity, learner outcomes, learner satisfaction with the experience of using the film watching activities. It also requires the knowledge and skills necessary to analyse, reflect, and re-design. All of this knowledge is rarely available in any way that could be considered systematic or deep. And a simple list like the above example doesn’t help.

Film Watching Options – a CASA solution

The following describes the Contextually Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA) approach we’ve developed. Currently labelled – Film Watching Options. As the same suggestions this approach is specific to this learning activity. It aims to embed good answers to the four questions outlined above into a collection of technology and practices that make it easier for the teacher to design, use and maintain a better quality learning space.

This isn’t a perfect solution. The current solution provides some ok answers to the first three questions, but doesn’t really offer any insight on the fourth questions. There is work to do. But it’s looking better than existing solutions.

Learner perspective

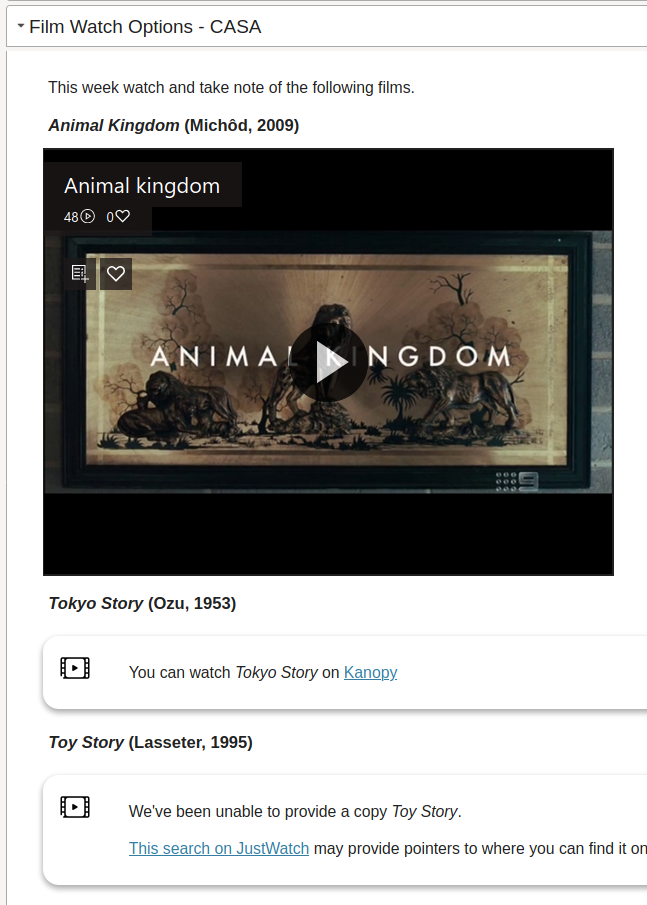

With the Film Watching Options approach, the learner doesn’t just see the list of films as shown above. Instead they see the following showing off three different options

- An embedded, ready to stream version of Animal Kingdom as provided by the institution.

- A link to a streaming version of Tokyo Story available in an online Film Collection.

- A link to a JustWatch search of streaming services available in Australia for Toy Story.

Option #3 illustrating what happens when the institution can’t provide access to a film and the learner has to go searching.

Teacher perspective

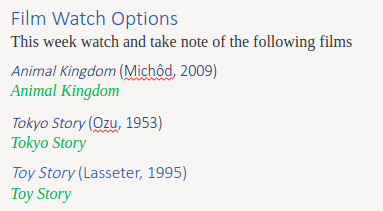

Currently the Film Watching Options feature is implemented as part of the Content Interface a Contextually Appropriate Scaffolding Assemblages (CASA) approach to using Microsoft Word to create and maintain course content. In this context, the teacher designing this learning space sees the following Word document when authoring. Notice the similarity between the Word document in the above below and the web page in the image above?

The idea is that when the teacher wants to provide film watching options to the learner they write (in Microsoft Word) the title of the film and then apply the Film Watching Options style. That’s why the film names in the above image are green. Prior to this the teacher, in collaboration with the library, will have create an Excel spreadsheet that has a table listing all the films in the course and if and where they are available online.

The technology perspective – how it works

From here the Film Watching Options and Content Interface CASA take over.

The Content Interface will translate the Word document edited by the teacher into the following HTML and embed it in the course site.

<h1>Film Watch Options - CASA</h1>

<p>This week watch and take note of the following films.</p>

<h3><em>Animal Kingdom</em> (Michôd, 2009)</h3>t

<div class="filmWatchingOptions">Animal Kingdom</div>

<h3><em>Tokyo Story</em> (Ozu, 1953)</h3>

<div class="filmWatchingOptions">Tokyo Story</div>

<h3><em>Toy Story</em> (Lasseter, 1995)</h3>

<div class="filmWatchingOptions">Toy Story</div>

When a learner views this page the Content Interface will find all the filmWatchingOptions elements and for each element

- Call a web service to discover what options exist for watching this films (by checking the Excel spreadsheet maintained by the teacher).

- Update the element to display the correct option.

Note: There wasn’t a “technology perspective” section for the current solution because it doesn’t actually do anything specific for this learning activity.

Next steps

Implementation within the Content Interface needs to be refined a touch. In particular, a lot more attention needs to be paid to figuring out if and how this approach can better help teachers answer question #4 above – How well did those films/activities work and what do I need to change for next time?

Longer term, I think there’s significant benefit from being gained implementing this type of approach using unbundled web components. Meaning I have to find time to engage with @btopro’s advice on learning more about web components.

Early implications

Even at this early stage there are two obvious early implications.

First, this makes it easier for the teacher to develop and improved learning space.

Second, these improvements provide affordances that generate unexpected outcomes. For example, the provision of the film specific JustWatch search helped me identify an oversight in a course. The course content listed a film as unavailable. The JustWatch search showed that the film was available via an institutional means. I was able to update the course content.

Broader possible implications

Design patterns have been suggested as a solution to the problem of educational design i.e.

There is a substaintial unmet demand for usable forms of guidance. In general, the demand from academic staff is for help with design – for customisable, re-usable ideas, not fixed, pre-packaged solutions. (Goodyear, 2005, p. 83)

One of the benefits of pattern languages is that they provide “a common language by which practitioners can share and discuss ideas” (Jones et al, 1999) associated with design. The object-oriented software design community is perhaps the best example of this. A community where practitioners use pattern names in design discussions.

Design patterns haven’t really entered mainstream practice in educational design practice. Perhaps because design patterns are bit too abstract/difficult for practitioners to embed in everyday practice. Perhaps picking up on Goodyear’s (2005) distinction between Long and short arc learning design. Some of the hypermedia design literature has previously made the connection between design patterns and constructive templates (Nanard, Nanard & Kahn, 1998). Constructive templates help make the connection between design and implementation. Perhaps this is (part of) the missing connection for design patterns in educational design?

What’s slowly evolving as part of the above work is the ability to start using names. In this case, film watching options is a nascent example of a name that is used to talk about this particular design/implementation solution. If it were implemented as an unbundled web component this would be reinforced further. Not to mention it would become even more customisable and reusable – echoing Goodyear’s description of the demand from teachers.

Might an approach like this implemented as web components help better bridge the gap between educational design and implementation? Might it provide a shared language that helps improve educational design? Might it help encourage the adoption of design patterns?

References

Biggs, J. (2012). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.642839

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1344

Goodyear, P. (2009). Teaching, technology and educational design: The architecture of productive learning environments (pp. 1–37). http://www.olt.gov.au/system/files/resources/Goodyear%2C P ALTC Fellowship report 2010.pdf

Goodyear, P. (2020). Design and co-configuration for hybrid learning: Theorising the practices of learning space design. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1045–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12925

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC Horizon Report: 2014 Higher Education Edition (No. 9780989733557). http://www.nmc.org/publications/2014-horizon-report-higher-ed

Jones, D., Stewart, S., & Power, L. (1999). Patterns: Using Proven Experience to Develop Online Learning. Proceedings of ASCILITE’1999. https://djon.es/blog/publications/patterns-using-proven-experience-to-develop-online-learning/

Jones, D., Heffernan, A., & Albion, P. R. (2015). TPACK as shared practice: Toward a research agenda. In D. Slykhuis & G. Marks (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2015 (pp. 3287–3294). AACE. http://www.editlib.org/p/150454/

Nanard, M., Nanard, J., & Kahn, P. (1998). Pushing Reuse in Hypermedia Design: Golden Rules, Design Patterns and Constructive Templates. 11–20.

Leave a Reply